WVE Fellows Artivism Projects

Combining art and activism to create the change we want to see.

Enjoy these artivism projects by WVE’s 2023-2024 Fellows.

Umyeena Bashir

California Intimate Care Organizing Fellow

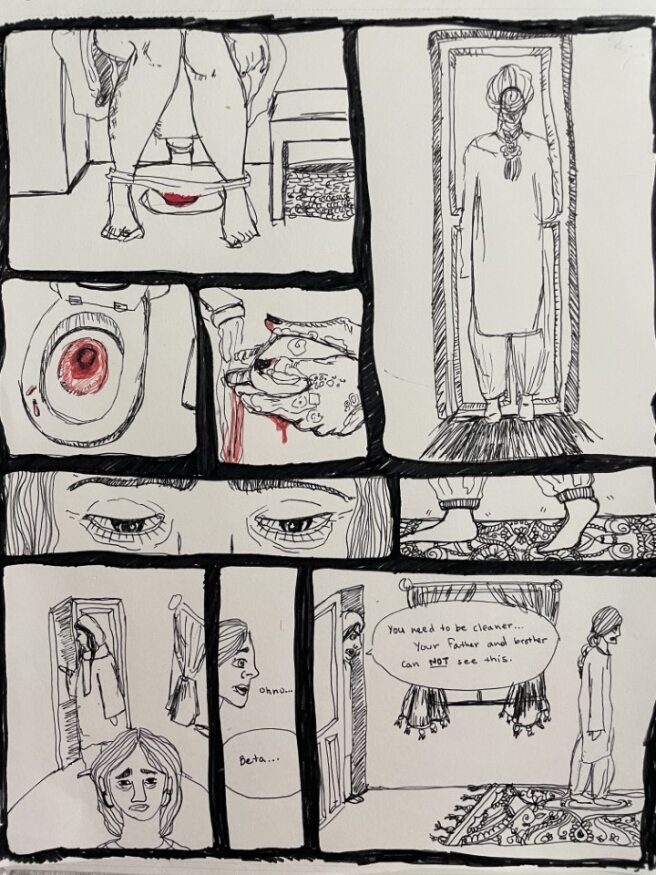

My Darkest Secret

Constant anxiety, stress for forgetting to prepare, and the worry of being caught are the ways I would describe my period journey as a kid. As a Muslim South Asian woman, my mother ingrained in me that my period was a secret. A secret that could never be shared or known to any man. If it were ever shared, I would face horrific shame. Hearing this at the young age of eleven years old, I tried my very hardest to keep that secret.

But, this was the hardest secret that I ever had to keep. I didn’t know what a burden it would have been. My everlasting stomach pains, the unbearable cramps, the nausea that would linger for days, it was so hard for me to keep these secrets. It felt like my secret was getting bigger and bigger as I got older. It hurt so much. However, I remained true to my cause because what was worse than letting go of my secret was the shame it would bring me. That fear I had ingrained in me is what truly got me to hold on so tight. My father and brother could never know when I was on my period. It would repulse them. They would look at me in disgust. I would be looked down upon. That fear forced me to keep my secret to myself.

10 years later, I finally let go of my secret for reasons I wish were not the cause. My younger sister was diagnosed with PCOS. This was the first time I had ever heard of this word. What is PCOS? What the doctor told us was that her hormones were irregular and because of that, she was experiencing irregular periods and abnormal levels of bleeding. It was a shock to get that phone call from my sister explaining this to me. However, what took me aback the most was when she told me if she had gone in earlier in her life to see a doctor, she could have prevented her infertility risks.

For 18 years my sister and I were hiding our secret, making sure no one knew what we were going through. But, hiding that secret is what caused all of this.

My story is not unique to many in our community. Thousands of South Asian menstruators are shamed into keeping their period a secret. The shame and taboo surrounding periods prevails to dominate over health. But why is this?

Over the past month, I interviewed three friends of mine that have PCOS and asked them about their PCOS journey. It wasn’t surprising to me that they all found out about their disease once going to the doctor without their parents around.

My close friend Sara told me, “I only found out I had PCOS when I went to the doctor myself as a legal adult, when my family was not present to block me from asking the questions I wanted to ask.” Her words resonated with me. As a child, whenever we went to the doctor, my Bengali mother always was present in the doctor’s room while I did check-ups. Whenever the pediatrician would ask about my period, I recall my mother answering for me as if to keep me quiet from telling her a truth that my mother didn’t want exposed. It took me years after to recognize what my mother was doing. But I never could understand why.

Why is it that my mother was harsh on me to not talk about my period in front of anyone? Was it a sign of weakness? Was it just gross? Or was it something else?

I discussed this with my friend Sonia who got diagnosed with PCOS at 18 with her sister present. When she answered, she said, “ I always believed it was because my mom thought it was a sign of sex. I mean, once you menstruate you become fertile. Back then, we would be considered ‘women of age’.”

What she told me intrigued me. I had never thought of it that way. I looked back on my life. And to think of it, my mother never told us about her period. We never even had ‘the talk’. How I learned about my period and what it was ironically by bleeding through white pants. I had run into the nurses office and that is when the nurse told me what a period was. Coming that day, I remember telling my mom and her not really saying anything. Her face was stoic. All she did was give me a box of pads and told me to be sure to not show my brother and dad. That was the end of any period conversation I ever had with her. Since that moment, all my puberty and menstrual struggles were not just a secret to my brother and father, but also a secret to my mother. I would not talk to her about any of my symptoms. And of anything, I could never murmur a word about my interest in boys. It was completely forbidden.

Maybe is was because my period was a sign of fertility and it freaked out my mother. Maybe she was just uncomfortable of the conversation. I don’t think I will ever truly know.

However, from all my conversations, it was clear to me, the secret of having a period had more burdens than one can imagine. It was clear keeping a period a secret was not worth any of the risks, the shame, the disgust that people claimed would be put on you.

If my sister was only able to speak up about her symptoms and pains about her period, she could have been treated earlier. Although she has started hormone therapy now, her risks are still high. If she only knew her period was not a secret.

Keana Davis

Keana Davis

Weavers Fellow

Re-think and Re-indigenize: Menstruation

For this project, I used my zine “Re-think and Re-indigenize: Menstruation” to explore advocacy and education around menstruation. Menstrual and reproductive health are so valuable and being able to make informed decisions has always been of the upmost importance for me as well as the normalization of differences individuals’ bodies—differences that have been targeted by patriarchal views as a means to define what is “feminine” or “sanitary” for bodies that are not their own. With the first half of the Zine focused on education, I wanted to include language and information that would not place judgment on people for their choice of menstrual products as safety and accessibility should be the top priorities.

When it comes to advocacy work, I value work that acknowledges the different access needs of individuals and accepts an individual in whatever stage of learning they are at. With broader research on the American Indian/Native Alaskan communities nationwide, the disparities that exist in resources are outstanding. Over the course of the years, I have learned more about my mother’s upbringing in Kayenta, AZ (Navajo Nation) and have learned about the changing landscape of the land today as my grandmother recounts memories shared at now abandoned buildings, fenced off land, and the naturalistic tourist attractions filled with white faces that are only passing through on their road trip. With my experience as a Diné different than that of my cousins who grew up on the reservation, my research moving towards urban AI/NA experiences and facts helped me gained insight into which direction I wanted my project to go.

Many urban AI/NA are faced with the loss of resources upon moving to urban areas as health programs, community programs, and spaces for cultural and traditional teachings are often lacking. For this reason, my zine focused on the movement of re-indigenization as every aspect of community and identity is valuable to the whole person. To be visible, to be connected, and to practice the teachings that honor your ancestors, your people, and the land is all a part of re-indigenization. Coming-of-age ceremonies like those shared within the zine are just some of the traditional teachings that have been demonized through colonization and are being revived by Indigenous communities.

Concerned about inclusivity with the contents of my project, I had decided to focus on American Indian identities as many of the resources based in the Bay Area use this as a common way to identify and address the community. I wanted to avoid attaching Native Alaskan to American Indian to create a Zine using “AI/NA” because I felt that this would suggest that Native Alaskan identities were an afterthought to my work. Using the term “indigenous” on page 7 was important to highlight that this movement of re-indigenization is not exclusive to just American Indians but also for communities worldwide due to the global effect of colonization. The discussion of coming-of-age ceremonies focused on menstruation utilizes the terms “girl” and “woman” to describe the transition that is celebrated within these communities. As important as it was to be gender neutral to account for menstruators of all identities, I knew it was not my place to strip these values that are built around community roles (men, women, two-spirit) within these cultures. In many reads related to narrative accounts of these ceremonies, it is often acknowledged the role of the whole community and the teachings offered by all members regardless of gender identity within these celebrations.

My incorporation of crocheted images became a way to tie in how my mother connected to her identity. Growing up, I had seen my mom crochet dresses for dolls with coloration inspired by American Indian cultures and handmaking miniature jewelry that resembled those my grandma would send for me. My mom, unable to speak Navajo fluently and separated from her community for many years, continued to connect with the culture in the ways she knew how and instilled pride in my sister and me for our identity.

Combining art and activism to create the change we want to see.

Enjoy these artivism projects by WVE’s 2021-2022 Fellows.

Umyeena Bashir

California Intimate Care Organizing Fellow

Umyeena Bashir is a graduate student at the University of San Francisco studying Organic Chemistry. She has expertise in chemical synthesis, organic research methods, and large scale data processing. Currently, she is working on developing new types of antibiotics against staph bacteria to address the rise in MRSA. Umyeena has a strong desire to address period stigma, period poverty, and proper menstrual care management. She has conducted research on period access, education and inclusivity and worked with local charities in her community to learn about the menstrual needs of the underserved. Read Umy’s blog post here and here.

Title Painting I: Honest Flower

The inspiration of this painting comes from the idea that a vagina is symbolized as a flower. This perception stigmatizes vaginas are delicate, soft, and fragile, perpetuating that vaginas are sacred. If something were to happen to this “flower”, it would be ruined. This metaphor of a vagina is problematic in that it fails to acknowledge the menstrual cycle, a very big part of the vaginal identity. Menstruation is not a ‘flowery’ process. Infact, for many it is painful, uncomfortable, and embarrassing. Thus, with this painting, I wanted to paint this stigma by painting the vagina as a dark flower with black and dark colors, taking in that the vagina is indeed beautiful, but menstruation (symbolized by the colors) is also a part of that identity.

[/gdlr_row]

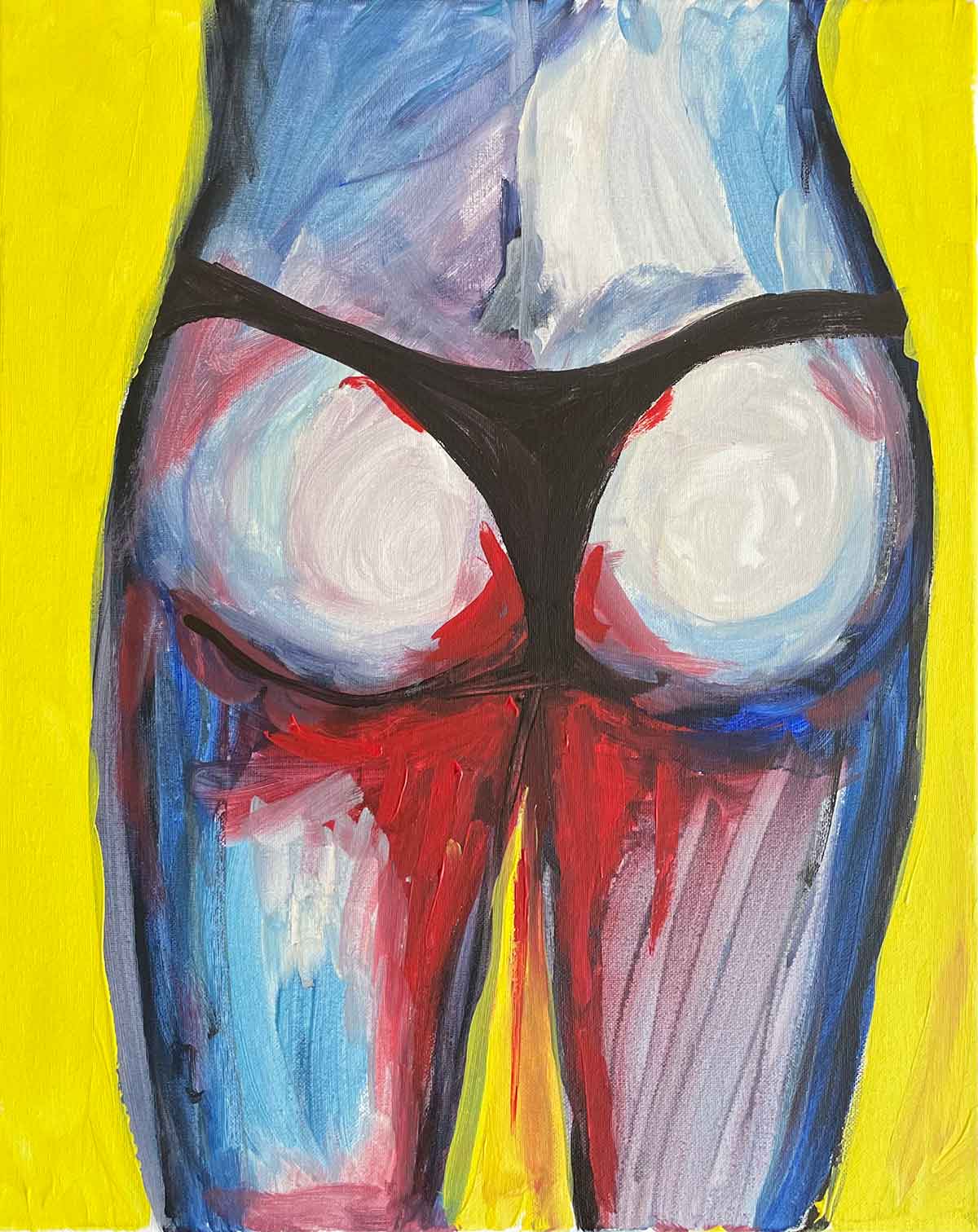

Title Painting II: Beach Water

The inspiration of this painting comes from a personal experience I witnessed. My friend and I were at the beach enjoying the San Diego sun. As we both got up to take a dip in the water, a man comes by and calls out to my friend and proceeds to cat-call her. She was very uncomfortable with his remarks. However, as she turned to face away from him, he started to squeal in the distance. He was shouting ”Ew that is just gross!” My friend then looked behind her back and noticed her period had started. From this incident, I wanted to paint an image that embodied that event in the way my friend was perceived and how menstruation is perceived. I chose primary colors to represent the basic nature of the woman body in a bold way. It brings attention to a woman’s figure, something that is often sexualized. The period blood dripping between the woman’s legs in this actualization of that a woman’s body is not just a sexual object but also is a human body that goes through natural biological processes. That is why the red blood is strong and very visible.

Mrittika Howlader

New York Intimate Care Organizing Fellow

Mrittika is a proud first-generation American woman. She is also a sophomore at Barnard College passionately double majoring in Human Rights and Women’s Studies. Whilst volunteering at the NYCLU, she, along with her peers, asked the tough questions to the next generation of policymakers and pushed for long-term structural change. She also led multiple peer education sessions with topics ranging from sex education to biometric surveillance and regularly participated in city-wide protests and campaigns. Read Mrittika’s blog posts on menstrual equity issues here and here.

Rena Chen

New York Intimate Care Organizing Fellow

Rena Chen is a Chinese American born and raised in the United States. She is currently attending Brooklyn Technical High School, studying medicine, but she is also passionate about humanitarian issues like women’s rights, reproductive care and equality for all races. Rena is the founder and president of the Period Awareness Club at her high school, which focuses on issues relating to menstrual care and equity, which hosts events that focus on bringing awareness and resolution to such disparities in society through education and action. Read Rena’s blog post, here.