Vaginal lubricants are popular and widely used products. Applied to the vagina, they work to increase lubrication of this sensitive area of the body. And while they can be very effective at reducing discomfort at the time they are used, researchers are becoming increasingly concerned about the potential longer term health effects of exposure to these products. Unfortunately, in many cases, not enough care has been taken to design lubricants that are truly safe and healthy for vaginal tissue.

Vaginal lubricants are popular and widely used products. Applied to the vagina, they work to increase lubrication of this sensitive area of the body. And while they can be very effective at reducing discomfort at the time they are used, researchers are becoming increasingly concerned about the potential longer term health effects of exposure to these products. Unfortunately, in many cases, not enough care has been taken to design lubricants that are truly safe and healthy for vaginal tissue.

What are Lubricants?

Vaginal lubricants are fluid substances designed to offset vaginal dryness or inadequate natural lubrication which can be associated with discomfort or pain. Vaginal dryness is experienced by many women and can result from a variety of conditions such as aging and menopause, breastfeeding, medical conditions such as diabetes and inflammatory bowel disease, and side effects of cancer treatment or other certain medications.[1] When asked in surveys, over 65% of women in the United States report using some form of vaginal lubricant in the previous month. [2][3]

What are the problems with lubricants?

Lubricants are generally effective for their intended use – to provide additional lubrication to vaginal tissue during sexual activity to decrease discomfort. However, vaginal exposure to lubricants can also have toxic side effects long after their use that pose considerable risk to reproductive health.

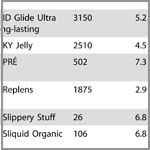

Like other intimate care products, there is a very specific route of exposure to these products as they are applied directly to the vagina. Recent research indicates that many lubricants on the market can have longer term detrimental effects on vaginal tissue. In fact, there is growing consensus among scientists that the vast majority of lubricants need to be reformulated to be safer than they are now.[4] In 2012, the World Health Organization issued an Advisory Note highlighting their concerns about the pH and osmolalities of lubricants, which included testing results of currently marketed lubricants. These concerns, were complemented by the work of several other researchers shortly after.[5][6][7]

Concerns with lubricants include:

pH: The pH of a lubricant represents how acidic or alkaline the product is. Ideally, the pH of a vaginal lubricant should be compatible with a healthy pH of the vagina – generally in the range of 3.8-4.5. A high vaginal pH (above 4.5) is associated with increased risk of bacterial vaginosis. Unfortunately, many commercially available lubricants have pH levels far exceeding 4.5.[8][9]

Osmolality – Osmolality refers to a substance’s ability to draw moisture out of tissues and cells. Exposure to a lubricant with a higher osmolality than normal vaginal secretions can result in vaginal tissue which literally shrivels up because the moisture in those cells is pulled out. This process leads to irritation and a breakdown of the mucous membrane barrier which protects the vagina from infection. Disrupted vaginal mucous membranes have been associated not only with irritation and discomfort but also with increased risks of sexually transmitted infections such as HIV. Unfortunately, many currently marketed lubricants have high osmolalities which are detrimental to vaginal tissue.[10][11]

Toxic chemicals found in lubricants:

Harsh chemical ingredients found in lubricants can also be toxic to vaginal tissue and its microbiome. (The microbiome is the balance of microorganisms that naturally inhabit the vagina.) Vaginal exposure to toxic lubricant ingredients can lead to discomfort, irritation, and increased risk of infection from even short term exposure. Some lubricant ingredients also have the potential to cause longer term chronic health effects including cancer and reproductive problems from repeated exposure over many years.

Chlorhexidine gluconate – This potent disinfectant chemical has been shown to kill off many strains of lactobacillus, a type of bacteria that, when in balance, are necessary for a healthy vagina.[12]

Parabens (commonly methylparaben and/or propylparaben) — These preservative chemicals have been shown to cause irritation of vaginal mucous membranes.[13] Exposure to parabens is associated with genital rashes.[14] Studies have also linked parabens to fertility problems and endocrine disruption.[15][16]

Cyclomethicone, cyclopentasiloxane and cyclotetrasiloxane — Commonly found in silicone-based lubricants, these substances are linked to reproductive harm and uterine cancer in animal studies. Almost no research has ever been conducted to examine the long term impacts of vaginal exposure to these chemicals in women.[17]

Undisclosed flavors or fragrance — The generic ingredients “flavor”, “fragrance” or “aroma” represent a combination of undisclosed chemicals. Numerous harmful chemicals can be included in flavors, fragrances, and aromas including carcinogens, reproductive toxins and allergens.[18]

Recommendations: How to find a safer lubricant that meets your needs

- Review the lists of lubricant testing results conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) and other researchers available here. These lists include brand names of lubricants and the pH levels and osmolalities of each product. The WHO recommends using a lubricant with a pH of 4.5 and an osmolality below 1200 mOsm/kg.

- If your brand of lubricant is not included in either of these lists, contact the manufacturer to ask about the pH and osmolality of the product and make sure they meet the WHO guidelines.

- Carefully examine the ingredients list for your lubricant and avoid products containing the chemicals of concern listed in this fact sheet.

- Avoid unnecessary “bells and whistles” like colors, fun flavors or heating/cooling/tingling features. The healthiest lube for your vagina is likely to be a simple one.

- Pay attention to any reactions or symptoms after you use a lubricant. Try switching brands if you notice irritation. You may be experiencing unnecessary discomfort and irritation due to the wrong choice of lubricant.

- Look for safer products! Check out our Business Partners.

Download and print this fact sheet.

[1] Edwards D and Panay N (2016) Treating vulvovaginal atrophy/genitourinary syndrome of menopause: how important is vaginal lubricant and moisturizer composition? Climacteric, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 151 –161. 2016

[2] Brown JM, Poirot E, Hess KL, Brown S, Vertucci M and Hezareh M. (2016) Motivations for Intravaginal Product Use among a Cohort of Women in Los Angeles. PLOS One. Vol. 11, No. 3. March 11, 2016.

[3] Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V, Sanders SA and Fortenberry JD. (2014) Women’s use and perceptions of commercial lubricants: prevalence and characteristics in a nationally representative sample of American adults. Journal of Sexual Medicine. Vol. 11, No.3, pp: 642-652. March 2014.

[4] Wolf, KL (2012) Studies raise questions about safety of personal lubricants. Chemical and Engineering News. Vol. 90. No. 50, pp. 46-47. December 10, 2012.

[5] World Health Organization (2012) Use and procurement of additional lubricants for male and female condoms: WHO/UNFPA/FHI360 Advisory note. Department of Reproductive Health and Research. 2012. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/76580/1/WHO_RHR_12.33_eng.pdf

[6] Dezzutti CS, Brown ER, Moncla B, Russo J, Cost M, Wang L, Uranker K, Kunjara Na Ayudhya RP, Pryke K, Pickett J, Leblanc MA and Rohan LC. (2012) Is wetter better? An evaluation of over-the-counter personal lubricants for safety and anti-HIV-1 activity. PLoS One.7(11):e48328. 2012. Available at: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0048328

[7] Cunha AR, Machado RM, Palmeira-de-Oliveira A, Martinez-de-Oliveira J, das Neves J, and Palmeira-de-Oliveira R (2014) Characterization of Commercially Available Vaginal Lubricants: A Safety Perspective. Pharmaceutics No. 6, pp. 530-542; 2014. Available at: http://www.mdpi.com/1999-4923/6/3/530

[8] World Health Organization (2012) Use and procurement of additional lubricants for male and female condoms: WHO/UNFPA/FHI360 Advisory note. Department of Reproductive Health and Research. 2012. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/76580/1/WHO_RHR_12.33_eng.pdf

[9] Cunha AR, Machado RM, Palmeira-de-Oliveira A, Martinez-de-Oliveira J, das Neves J, and Palmeira-de-Oliveira R (2014) Characterization of Commercially Available Vaginal Lubricants: A Safety Perspective. Pharmaceutics No. 6, pp. 530-542; 2014.

[10] Dezzutti CS, Brown ER, Moncla B, Russo J, Cost M, Wang L, Uranker K, Kunjara Na Ayudhya RP, Pryke K, Pickett J, Leblanc MA and Rohan LC. (2012) Is wetter better? An evaluation of over-the-counter personal lubricants for safety and anti-HIV-1 activity. PLoS One.7(11):e48328. 2012. Available at: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0048328

[11] World Health Organization (2012) Use and procurement of additional lubricants for male and female condoms: WHO/UNFPA/FHI360 Advisory note. Department of Reproductive Health and Research. 2012. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/76580/1/WHO_RHR_12.33_eng.pdf

[12] Dezzutti CS, Brown ER, Moncla B, Russo J, Cost M, Wang L, Uranker K, Kunjara Na Ayudhya RP, Pryke K, Pickett J, Leblanc MA and Rohan LC. (2012) Is wetter better? An evaluation of over-the-counter personal lubricants for safety and anti-HIV-1 activity. PLoS One.7(11):e48328. 2012. Available at: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0048328

[13] Gali,Y, Delezay O, Brouwers J, Addad N, Augustijns P, Bourlet T, Hamzeh-Cognasse H, Arien KK, Pozzetto B and Vanham G. (2010) In Vitro Evaluation of Viability, Integrity, and Inflammation in Genital Epithelia upon Exposure to Pharmaceutical Excipients and Candidate Microbicides. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Vol. 54, No. 12, pp. 5105–5114. Dec. 2010.

[14] Bauer, A, Geier, J and Elsner, P. (2000) Allergic Contact Dermatitis in Patients with Anogenital Complaints. The Journalof Reproductive Medicine. Vol. 45, No.8, pp:649-654. August 2000.

[15] Darbre P.D. and Harvey P.W. (2008) Paraben esters: review of recent studies of endocrine toxicity, absorption, esterase and human exposure, and discussion of potential human health risks. Journal of Applied Toxicology. Vol. 28, No. 5, pp:561-578. July 2008.

[16] Smith, KW, Souter, I, Ehrlich,S, Williams, PL, Calafat, AM and Hauser, R. (2013) Urinary paraben concentrations and ovarian aging among women from a fertility center. Environmental Health Perspectives. Vol. 121, Issue 11-12, pp. 1299-1305. December 2013.

[17] SCCS (Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety) (2016) Opinion on decamethylcyclopentasiloxane (cyclopentasiloxane, D5) in cosmetic products, SCCS/1549/15, 25 March 2015, final version of 29 July 2016 Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/health//sites/health/files/scientific_committees/consumer_safety/docs/sccs_o_174.pdf

[18] Women’s Voices for the Earth (2015) Fragrance Chemicals of Concern Present on the IFRA List 2015. Available at: https://womensvoices.org/fragrance-ingredients/fragrance-chemicals-of-concern-on-ifra-list/